“I know well that I have it in me to make my name famous. No man lives or has ever lived who has brought the same amount of study and of natural talent to the detection of crime which I have done.”–Sherlock Holmes

“I know well that I have it in me to make my name famous. No man lives or has ever lived who has brought the same amount of study and of natural talent to the detection of crime which I have done.”–Sherlock Holmes

Everyone knows Sherlock Holmes. His name is a byword. His fame is universal. His career is legendary. His features are immediately identifiable—or are they? The iconic silhouette with the deerstalker cap and the calabash pipe. Elementary, my dear Watson.

On the contrary, however, and to quote the good doctor, “Desultory readers are seldom remarkable for the exactness of their learning.” Civilized readers are another matter.

Nowhere in the Sacred Writings is a deerstalker mentioned. Further, the clay churchwarden was a clear preference of the Baker Street sleuth. As for the immortal quote, the sentence never appears in the Canon. (The word “Elementary” is spoken by Mr. Holmes in closest conjunction to his saying “my dear Watson” in “The Adventure of the Crooked Man,” where they are separated by fifty-two words.) Does anyone really know Sherlock Holmes?

Sherlock Holmes is a classic example of one conquered by his own greatness, reduced by the height of his clout into a cliché. Everyone recognizes him but knows nothing of him. Few have had a proper introduction to the Master. And the only proper introduction to Mr. Holmes for civilized readers is by meeting him with Dr. Watson. And the only place to receive that introduction is in A Study in Scarlet.

A Study in Scarlet, the very first of the Sherlock Holmes stories, offers some of the best insights into this man who is more of a mystery than the mysteries he reduces to simple facts. Holmes’s methods of observation and deduction are generally known, but not so much his madness. Anyone with a nodding acquaintance can say something about his violin or his magnifying glass or his laboratory—all of which make their first appearance in the first case—but what of his beating corpses in the morgue to see how long bruises can be produced after death? What of his indifferent ignorance of the solar system? Or his silent, brooding depression? Once the simplification engendered by his popularity lifts like a London fog, Sherlock Holmes emerges as a figure of astonishing complexity.

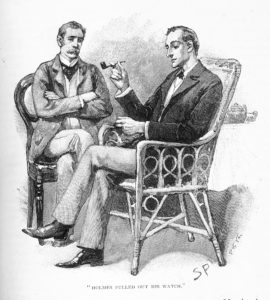

A Study in Scarlet is first and foremost a mystery about a man before it is a mystery about a murder, and Dr. Watson is the detective who finds himself on the trail of another detective. After suffering a gunshot wound in the Battle of Maiwand, Dr. Watson arrives to recover in London, “that great cesspool into which all the loungers of the Empire are irresistibly drained.” The bowlered army doctor with a “bull pup” soon takes up rooms at 221B Baker Street with an extraordinary fellow he meets by happenstance.

His very person and appearance were such as to strike the attention of the most casual observer. In height he was rather over six feet, and so excessively lean that he seemed to be considerably taller. His eyes were sharp and piercing, save during those intervals of torpor to which I have alluded; and his thin, hawk-like nose gave his whole expression an air of alertness and decision. His chin, too, had the prominence and squareness which mark the man of determination. His hands were invariably blotted with ink and stained with chemicals, yet he was possessed of extraordinary delicacy of touch, as I frequently had occasion to observe when I watched him manipulating his fragile philosophical instruments.

Before long, Watson becomes bent upon unlocking the secret of the eccentric character he has taken diggings with. His notes on Mr. Sherlock Holmes are both instructive and intriguing:

SHERLOCK HOLMES—his limits

-

- Knowledge of Literature.—Nil.

- ” ” Philosophy.—Nil.

- ” ” Astronomy.—Nil.

- ” ” Politics.—Feeble.

- ” ” Botany.—Variable. Well up in belladonna, opium, and poisons generally. Knows nothing of practical gardening.

- ” ” Geology.—Practical, but limited. Tells at a glance different soils from each other. After walks has shown me splashes upon his trousers, and told me by their colour and consistence in what part of London he had received them.

- ” ” Chemistry.—Profound.

- ” ” Anatomy.—Accurate, but unsystematic.

- ” ” Sensational Literature.—Immense. He appears to know every detail of every horror perpetrated in the century.

- Plays the violin well.

- Is an expert singlestick player, boxer, and swordsman.

- Has a good practical knowledge of British law.

Watson conjectures that a revelation of Holmes’s character will further disclose his occupation, which is the only thing more mysterious than the man himself. The Baker Street rooms are constantly being visited by police-jawed men, weeping women, seedy ruffians and whatnot, all filling Watson with a temptation to betray his English delicacy as he is repeatedly asked, with all English grace, to make allowance for his companion’s professional privacy. The honest persistence of Dr. Watson is immediately apparent, as he demonstrates why he is, by his firm and frank personality, the perfect foil to Holmes’s flighty and flamboyant genius.

When the truth of these investigations finally comes out—that Sherlock Holmes is a consulting detective—Watson is immediately whisked along on one of his friend’s cases. They fly through the dull morning to Lauriston Gardens, off the Brixton Road, to an abandoned house in which was discovered the body of a man with limbs and face contorted in the spasms of a violent death, but with no wound, lying in a room splashed red with blood, the red letters RACHE scrawled in trickling blood on the wall, a woman’s wedding ring on the red-spattered floor, and a red candle standing in the corner.

And with that cryptic, crimson scene, it all begins. “There’s the scarlet thread of murder running through the colourless skein of life, and our duty is to unravel it, and isolate it, and expose every inch of it.” In further calling the grotesque scene “a study in scarlet,” Mr. Holmes’s “art jargon” may have inadvertently inspired Dr. Watson to the literary action of becoming a Boswell, with reminiscences which would prove too romantic for Holmes’s rigid views. The tale is indeed a tangled skein (as the novel was originally titled), and full of moments that have become quintessential and a pleasure to witness as occurring for the first time—from Holmes revealing the inner man by analyzing his outward appearance to Watson being told to put his pistol in his pocket. It all begins with A Study in Scarlet.

A Study in Scarlet is, therefore, an indispensable introduction to an ingenious character and an ingenious career. In 1886, a struggling 27-year-old physician named Arthur Conan Doyle made a fateful decision which was intended simply to pay the bills, but which would end up enriching the world. He published a novella featuring an eccentric consulting detective by the name of Sherlock Holmes. With A Study in Scarlet appearing in Beeton’s Christmas Annual in 1887, the stage was set for what would prove one of the greatest archetypical creations in the history of literature.

By 1893, Sherlock Holmes was an unprecedented sensation, but his inscrutability is why he endures. Holmes’s mystique is the mystery of mysteries, and the scene of that mystery is set in A Study in Scarlet. The endless paradoxes and complexities of Holmes have given rise to a fascination to crack the case of this extraordinary man, to comb Watson’s memoirs for clues uncovering Holmes’s history and his inmost character, to systematically eliminate the impossible until the truth, however improbable, remains. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle gave the world sixty Sherlock Holmes mysteries; but more importantly, he gave the world the mystery of Sherlock Holmes. And there can be no true beginning to any study in Sherlock Holmes without first A Study in Scarlet.