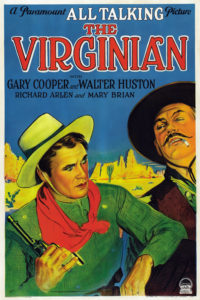

What is manliness in relation to Christian virtue or societal influence? Is there any way to speak of authentic masculinity without at least implicitly drawing from the Ten Commandments, the cardinal virtues, or an established moral code of some religion or society? It is a question especially pertinent in a time when the concept of masculinity is met with such distrust from the media and the broader populace. Moreover, the question of what it is to be a man is one which men of all ages ask themselves, consciously or not, as they age. It is something rarely addressed explicitly in the lives of the saints. The answer to the perennial question cannot be simply, “Be a good Christian and you’ll be a good man.” Otherwise, there would be no difference between a feminine and masculine practice of Christianity. There must be a special ruling quality to masculinity, just as there must be one for femininity, which directs one’s other virtues and makes them essentially masculine or feminine. The quest for these answers takes place throughout The Virginian by Owen Wister.

What is manliness in relation to Christian virtue or societal influence? Is there any way to speak of authentic masculinity without at least implicitly drawing from the Ten Commandments, the cardinal virtues, or an established moral code of some religion or society? It is a question especially pertinent in a time when the concept of masculinity is met with such distrust from the media and the broader populace. Moreover, the question of what it is to be a man is one which men of all ages ask themselves, consciously or not, as they age. It is something rarely addressed explicitly in the lives of the saints. The answer to the perennial question cannot be simply, “Be a good Christian and you’ll be a good man.” Otherwise, there would be no difference between a feminine and masculine practice of Christianity. There must be a special ruling quality to masculinity, just as there must be one for femininity, which directs one’s other virtues and makes them essentially masculine or feminine. The quest for these answers takes place throughout The Virginian by Owen Wister.

Even though he is widely recognized as the father of Western fiction, Wister is not just another cowboy novelist, writing what equates to a regency romance novel with pistols and spurs. Hailing from Pennsylvania, educated at Harvard Law, and having frequent travelled to the Western frontier in the days when there was a great deal more wilderness and pioneering, Wister was deeply fascinated with the differences between Eastern and Western customs, Christian and agnostic. The narrator of The Virginian, an agnostic Easterner who slowly becomes accustomed to the ways of the West, might well be Wister himself. When you prune away influences of a country or religion, what is that thing that is identifiable as the man, regardless of social conventions and religious morality? Can both the Easterner, well-versed in what Jane Austen would call “the civilities” of polite company, and the Westerner, untamed and carrying a pistol at his hip for protection, be equally manly?

The inquiry surrounds the titular character of the novel, a man known as “the Virginian.” The first chapter draws more attention to his easy-going sense of humor and his respect for truth than to his pistol. Stepping off the train into the virgin wilderness of Wyoming for the first time, the first-person narrator from the East is distracted away from his lost baggage by a scene taking place on the boarding platform, the likes of which he has never before seen.

“Off to get married again? Oh, don’t!” The voice was Southern and gentle and drawling; and a second voice came in immediate answer, cracked and querulous:—“It ain’t again. Who says it’s again? Who told you, anyway?” And the voice responded caressingly:—“Why, your Sunday clothes told me, Uncle Hughey. They are speaking mighty loud o’ nuptials.”

The narrator takes pleasure in being the onlooker of this verbal sparring session, until his status is changed to active participant. The Southerner looks him up and down and says, “I reckon I am looking for you, seh.” The Southerner no longer has the smile from the exchange with Uncle Hughey on his face, but rather the serious deportment of one entrusted with a job he intends to do well: he is to lead this man to his employer’s ranch safely, well over two hundred miles away from the train station.

The narrator tries to pretend friendship (and therefore equality) by expressing his appreciation of how handily the man had routed Uncle Hughey, but the Virginian will have none of it. The Virginian is perfectly courteous, but nothing more. They don’t know each other, so why should they pretend to be old friends? Wouldn’t that be akin to lying? Rebuffed in his initial advances, the narrator makes one last attempt at the Eastern habit of easy intimacy: “Find many oddities out here like Uncle Hughey?” “Yes, seh, there is a right smart of oddities around. They come in on every train.” Considering that he himself came in on the last train, the jab does not go unnoticed. From this point on the narrator is no longer allowed to merely be an outside observer, above the questions that take place in the novel, watching the Virginian poke fun at oddities like Uncle Hughey; he has to walk in that world and be judged an equal, an oddity, or worse. The narrator must earn that friendship and equality, for it would have little value if it was given out indiscriminately.

A Bostonian through and through, the narrator has much self-evaluation to undergo when living side by side with men bred in a wild territory. What man would not question his own masculinity when surrounded by men unlike himself, toughened by hard work and made skillful in many things through the necessity of their kind of work? His stiff Eastern clothes in the company of cattle men earn him the nickname “the Prince of Wales” and his helplessness in survival and navigation make him known as “the tenderfoot.”

And yet he is no straw man, signifying some shallow Easterner in the face of the rock solid virility of Westerners. While he must learn how to ride, travel the wilderness without a guide, and handle himself amidst the idioms and code of cow punchers, he also serves as a valuable contrast to the men who live in an unsettled territory. The Westerners may be more attuned to the land and the signs of nature, but the narrator comes from the cultural and educational capital of the United States, and it shows. And at times the Westerners—including the Virginian—reveal themselves to be just as prejudiced to Easterners as the reverse.

The narrator’s early reflections are telling in this regard:

I have thought that matters of dress and speech should not carry with them so much mistrust in our democracy; thieves are presumed innocent until proven guilty, but a starched collar is condemned at once. Perfect civility and obligingness I certainly did receive from the Virginian, only not one word of fellowship.

At times, the cultivation of the narrator highlights what is lost in such a new country, but his ineptitude in practical skills calls the sacrifice of the wilderness into question.

The contrast the novel makes between Boston and Wyoming leaves the reader constantly asking what is lost by hundreds of years of settlement and conventions, as well as what is missing in a newly-begun colony. To be sure, Wister attempts no Rousseauian experiment. The Virginian is not the wildman, free of the shackles of civilization and finally able to express the raw strength and happiness to be found in such a state of nature. But neither does he let the years of accumulated Eastern conventions go without a critical eye. Rather, Wister puts East and West on the extreme ends of a horizontal line and attempts to find where on that line human flourishing is best cultivated.

While the narrator’s formal education is undeniably superior to the Virginian’s, it is no easy matter to settle who is wiser. In the first few minutes of their acquaintance, the Southerner teaches the narrator the value of friendship by not offering it out like candy. If it is worth having, then it is worth earning. Later, during the ensuing ride to Judge Henry’s ranch, the narrator, ill-accustomed to long periods of silence, tries to fill the silent hours with conversation. While conversation is not bad in itself, his desire for it arises more from his inability to reflect and keep to his own thoughts than from a healthy desire for human society. Responding to his questions with one-word answers, the Virginian teaches him the value of silence and reflection, though there is no intention “to teach this Easterner a lesson.” Who has not bumped into the chatty man that cannot seem to abide quiet, and thought him effeminate? And yet, the narrator’s cultivation gives him quite an edge.

In fact, a keen mind proves to be no mean gift in cattle land. From the stereotype of Westerns, one might expect that courage, bullets, and grit are the highest virtues, but that is not realistic. The chief battles in this novel are of wit, not of bullets. It becomes clear that one can only become a good leader of men with a keen intelligence, but not the sort that books give, though they can certainly help. There is another type of knowledge gained from experience of the world, a clean heart, and courage. Some have a clean heart and courage, but no experience, and they make some dangerous blunders. Others have a clean heart, but no experience or courage, and it ends badly for them. And then there are those who have only experience. The novel features each of these types.

Though the Southerner is agnostic, he has some thought[provoking reflections on faith. It is a treat to imagine grounded cowboys interacting with a goodhearted but disconnected missionary. Readers cringe and laugh at the same time when Dr. MacBride, a missionary to what he considers “a desolate and mainly godless country,” is introduced. Sitting patiently and quietly indulging Dr. MacBride as he holds forth on what he deems necessary for these hard-working yet mischievous cowboys, the congregation hears these and like honey-tongued sentiments of salvation:

The cow-boys were told that not only could they do no good, but that if they did contrive to, it would not help them. . . . Their sin was indeed the cause of their damnation, yet, keeping from sin, they might nevertheless be lost. It had all been settled for them before they were born, but before Adam was shaped. Having told them this, he invited them to glorify the creator of this scheme. Even if damned, they must praise the person who made them expressly for damnation.

As with any audience of a sensible persuasion, these sentiments have a predictable effect. The cowboys walk back to their bunkhouse wryly joking: “Well, I’m going to quit fleeing temptation.”—“That’s so! Better get it in the neck after a good time then a poor one.” When a mischievous cowboys has better manners than his catechist, one wonders what he has that his pastor does not.

Scenes rife with similar questions (and there are many like it) fill the novel, and it is in scenes like these that compelling questions arise about the specific role of masculinity. For instance, does not the Virginian’s reserve during his first meeting with the narrator smack of a lack of charity? Doesn’t the Christian apostolate urge, nay, necessitate that we strip aside all our own preferences for even good things like silence for the sake of reaching our neighbor? Shouldn’t the Virginian put aside any personal discomforts and insults for the sake of helping his neighbor, and if he does not, how is this manly? Yet, there is something quite masculine and natural in the Virginian’s calm reserve that is not simply the romantic effect of the cowboy. The narrator deserves to be put in his place and he profits from this, as he later recalls. The Virginian is not rude, but neither is he friendly.

After three hundred pages of observing this gentle cowboy, one begins to ask himself if he needs to reevaluate some of his notions of manhood and charity. Does Christianity require us to be friendly? Is friendliness the same thing as charity? The Virginian does have friends, as the reader finds out. Half the enjoyment of the novel is seeing how differently this Southerner treats the cast of characters that come into his purview: friends, colleagues, superiors, subordinates, and enemies. Be warned, though: like the narrator, you won’t ever be able to be simply a spectator to the story. Readers will either be inspired by, shamed by, or disdainful of the Virginian; they cannot ignore him.