My dark and cloudy words, they do but hold

The truth, as cabinets enclose the gold.

—Pilgrim’s Progress

A generation or two ago, it would not have been necessary to remind anyone who John Bunyan was. Since 1912, a memorial window depicting eight scenes from his most famous work, The Pilgrim’s Progress, has graced Westminster Abbey. At the hands of Ralph Vaughn Williams in 1951, this same work was piled up into a regular thunderhead of an opera. For several generations of students, The Pilgrim’s Progress was a pillar of literary studies in both England and America. Once upon a time, Bunyan’s readership nearly overtook the Bible—and certainly the bard— in popularity. Yet I wonder how many of my students today would recognize his name as readily as they would that of Shakespeare.

This Lent, I picked up Pilgrim’s Progress for the first time. My edition was printed (really printed!) in the early twentieth century by a  publishing house that seemed to specialize in romantic poets (Keats, Burns, Tennyson), adventure stories (mostly Sir Walter Scott), and histories of painting (Boticelli, Rossetti, etc.). Peeping up between the bread-and-butter selections were a few volumes with titles like English Rock Gardening and The TransVaal War. But between the red- and gold-leaf covers of the book were some lovely plates by British illustrator Byam Shaw. As spiritual reading goes, the volume was hardly penitential looking.

publishing house that seemed to specialize in romantic poets (Keats, Burns, Tennyson), adventure stories (mostly Sir Walter Scott), and histories of painting (Boticelli, Rossetti, etc.). Peeping up between the bread-and-butter selections were a few volumes with titles like English Rock Gardening and The TransVaal War. But between the red- and gold-leaf covers of the book were some lovely plates by British illustrator Byam Shaw. As spiritual reading goes, the volume was hardly penitential looking.

Critics commonly note the vast number of authors whose literary bloodlines run back to Bunyan, a nearly Homeric catalogue of writers from Thackeray and Hawthorne to Lewis and Twain. Yet as we read the book, we recognize that Bunyan has also stolen the signposts and paving stones of his spiritual Aeneid from nearly all the ruined cities of antiquity, be they Troy, Rome, or Jerusalem.

Although his most agreed-upon influences were assorted romances, the Authorised (King James) Version of the Bible, and works of spiritual direction, it is almost impossible to read the following lines without thinking of pious, long-suffering Aeneas:

As I walked through the wilderness of this world, I lighted on a certain place where was a Den, and I laid me down in that place to sleep: and, as I slept, I dreamed a dream. I dreamed, and behold, I saw a man clothed with rags, standing in a certain place, with his face from his own house, a book in his hand, and a great burden upon his back. I looked, and saw him open the book, and read therein; and, as he read, he wept, and trembled; and, not being able longer to contain, he brake out with a lamentable cry, saying, “What shall I do?”

Upon re-reading, one might even catch a glimpse of Dante midway through the path of life, of Aeneas burdened by the weight of Troy, or of the Christ atop Gethsemane—Although, as Samuel Johnson kindly notes for us: “there was no translation of Dante when Bunyan wrote.”

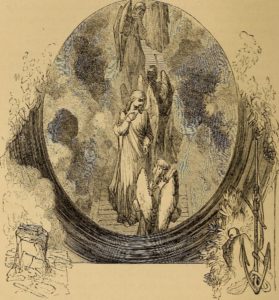

Bunyan begins his Reformed epic in medias res—that is, in the middle of his own imprisonment. He wrote Pilgrim’s Progress from a Bedford prison, serving out his sentence after being jailed for preaching without a license. The very first lines refer to a “Den,” and the frontispiece of the third edition (1679) shows the author napping pensively atop a Den, complete with both a portcullis and a rather peckish looking lion. In fact, the whole work seems to be related to the Book of Daniel, and perhaps to this one passage in particular: “My God sent his angel, and he shut the mouths of the lions. They have not hurt me, because I was found innocent in his sight.” (Dan. 6:22) Lions and predatory forces of all types assault Christian, the pilgrim, as he treks toward the celestial city. Bunyan languishes in jail, aware of the divine portion that his suffering permits him to grasp. One might even say that the author’s “entombment” in the Bedford Gaol permitted him to begin his interior quest towards the “Celestial City,” through a long and frequently horrifying journey toward the ultimate death-to-self.

Bunyan begins his Reformed epic in medias res—that is, in the middle of his own imprisonment. He wrote Pilgrim’s Progress from a Bedford prison, serving out his sentence after being jailed for preaching without a license. The very first lines refer to a “Den,” and the frontispiece of the third edition (1679) shows the author napping pensively atop a Den, complete with both a portcullis and a rather peckish looking lion. In fact, the whole work seems to be related to the Book of Daniel, and perhaps to this one passage in particular: “My God sent his angel, and he shut the mouths of the lions. They have not hurt me, because I was found innocent in his sight.” (Dan. 6:22) Lions and predatory forces of all types assault Christian, the pilgrim, as he treks toward the celestial city. Bunyan languishes in jail, aware of the divine portion that his suffering permits him to grasp. One might even say that the author’s “entombment” in the Bedford Gaol permitted him to begin his interior quest towards the “Celestial City,” through a long and frequently horrifying journey toward the ultimate death-to-self.

Part of the reason that this is so true of Pilgrim’s Progress is that the universality and romance of Bunyan is co-mingled with an ordinariness, a stolidity and firmness that comes from the basic (but not “simple”) devotion of an ordinary man to an extraordinary spiritual quest. It is the kind of mixture that appears in few men—St. John Henry Newman, for example. In Bunyan, we do not meet with historical characters who have become the embodiment of universal vice, as in the case of Dante’s Count Ugolino. In fact, the situation is the reverse. Masters Christian, Faith, Hope, and Mistresses Christiana and Mercy, Masters Pliable and Ignorance, Mr. By-Ends and Worldly Wiseman, Judge Hate-Good and Talkative at first sight might seem, as we read the cover flap (or cheat ourselves by reading the encyclopedia entry before the book itself), mere reductions of a fuller humanity: crude, abstract, and allegorical.

Yet on further acquaintance, we realize exactly how full of life these creatures are. These are men as we have seen them in our own lives: they swear they are on the right path, yet are so self-deluded as to be incapable of seeing good in others, or evil in themselves. There are no fully evil characters along the Pilgrim’s journey, as there are no perfectly good ones, save, respectively, the devils and angels. Everyone else is immersed in the deadly drama of salvation. Everything is at stake. There is no danger that does not press upon Christian at every step of the way; and lest we take too much confidence in the character’s name, Bunyan constantly reminds us how easy it is to appear Christian, and yet be set upon the road to Hell. Christian seems to embody the struggle of St. Paul: “For the good that I would I do not: but the evil which I would not, that I do.” And yet Christian struggles onward, delivered in each case by grace.

The work is a perfect depiction of the idea that life is a test given by God, an athletic event, with a prize that few can attain. Bunyan does not sugarcoat the fact that most of mankind are joined to the massa damnata. But he also clearly wishes to show us, in “fancies” that “stick like burs,” the way out. We are brought into Christian’s world and, better: we are brought out of it.

It is in cases like this that art seems to be of its highest value, and at its most “sacramental,” since the work of art in question can be used almost liturgically. The work “effects what it signifies” in readers, in an analogous way to the sacraments. All good art does. When we follow the devotion of the Stations of the Cross, what are we doing but effecting, in a sense, the signified crucifixion of Christ in our very selves? Such, in my belief, is part of Bunyan’s artistic motive. As we read it, we become more and more convinced that the writing is not merely allegory, but a representation of Christ’s suffering, which we recognize as identical, not only with Bunyan’s Christian, but our own. In other words: The Pilgrim’s Progress was not merely meant to be literature; it was meant to be read, and then to be lived. Christian’s spiritual journey is our own.

If I have left certain aspects of Bunyan’s work untreated—his anti-papalism, his potentially Calvinist leanings—it is partly because we ought to read Bunyan charitably. His conversion, about which he has written at great length, and his own pilgrimage were truly sincere. We find in both his life and his writings certain qualities which are shared by the Scriptures themselves: pleasing, elevated, and (deceptively) simple style and method of thought, rich in imagery and parable. He seems even to have been privy to visions, much like the equally eccentric William Blake.

It is also partly because, to badly paraphrase St. John Henry Newman, a really successful essay must be one-sided if it is to be effective. The essayist ought to look through one facet of reality, and not attempt the expansive universality of the philosopher. I want us to read Bunyan, and not merely catalogue him neatly somewhere along our mental shelves, in the section disapprovingly labelled “heretic authors.” It is a favor that he himself asks of us, in his concluding verse:

Take heed, also, that thou be not extreme,

In playing with the outside of my dream:

Nor let my figure or similitude

Put thee into a laughter or a feud.

Leave this for boys and fools; but as for thee,

Do thou the substance of my matter see.

Put by the curtains, look within my veil,

Turn up my metaphors, and do not fail,

There, if thou seekest them, such things to find,

As will be helpful to an honest mind.

What of my dross thou findest there, be bold

To throw away, but yet preserve the gold;

What if my gold be wrapped up in ore?—

None throws away the apple for the core.

But if thou shalt cast all away as vain,

I know not but ’twill make me dream again